“O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams."

— Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2.

SHADOW

In one of my earliest, most stubbornly unshakeable memories I am four years old. In this scene, I am lying in my childhood bedroom in Victoria Garden City, Lagos. I had the top bunk, covered in unlicensed Pokemon bedding. The figures of my 1997 Dekker Toys ‘Adventures of Batman and Robin’ projector have escaped their celluloid bounds and transformed into warped, menacing silhouettes on the pale blue walls. They appear to me as monsters, twisted versions of their cartoon analogues.

In the decades since, this night has visited me many times, as many kinds of nightmare. Lying in bed, sober as a judge, I have hallucinated screams, felt the grotesque sensation of claws grabbing at my wrists—believing for a moment that the devil himself was in my bed. I have lain paralysed, suffocating. I have frequently jerked awake, sheets drenched in sweat. Furnishings have become inhuman, but living shadows, perilous phantoms. Clothes on hangers have become corpses on meathooks. I have dreamed vividly, extensively, and often of death.

Sometimes this is a vague sense of pain and ending, some nebulous, intangible threat. Sometimes a strangely detailed scenario appears to me. A few days ago I dreamt there was a mass shooting. I was one of three survivors, but the incident had left me with a painful permanent tic: the right side of my face would without warning stretch into a painful grimace—a ghastly and ironic inversion of the very real bell’s palsy that had struck twice before I emerged out of adolescence.

Alongside this there have been sweet illusions too: a fur coat in my bedroom transformed into a huge, magnificent, black labrador, lucid dreams—flight, passion, full-throated godhood—a universe unfurled to me and sometimes mastered. But more often than not, on the nights when my body has broken with reality, it has raised hell.

But all dreams end. At night, the shadows may descend but they are dispersed by sunrise, and breath finds purchase, as if for the first time, in my body. I ride the escalator skyward, borne into the roaring noise of the day. The nightmares have long failed to scare me in any meaningful way. The potential terrors of my waking hours are a far more dreadful cloud than anything my mind might conjure up when it rests on my pillow.

“It is intolerable to have one's sufferings twinned with anybody else's.”

― Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others

SPECTRE

The first time I thought about killing myself, or perhaps named the thought clearly to be more accurate, I was somewhere between eleven and fourteen. Catholicism prohibits this, of course. There is no doctrine that sanctions this kind of self-sacrifice. Mine would be a body on the outskirts of the church, too damned for consecrated ground. I wanted a workaround: death without hell, without the shame self-infliction would leave in its wake. I prayed for cancer, for accident, for an end by nature or a hand more divine—less weak and blameful than mine. My desire for death was nebulous. It seemed to float over me, beside me. A passive but near-constant presence that endures with me still, to this day. In death, my mind says, I could not disappoint as I do in life.

I have only very recently been diagnosed with something I now think I had sensed for a long time, maybe my whole life, but did not have the language for. I have Borderline Personality Disorder. Some with these traits bristle at the categorisation. There is a great deal of stigma attached to the label. "I say what your mother has, at the very least, is what we call borderline personality disorder," begins Dr Melfi, Tony Soprano's long-suffering therapist on the cult classic HBO Drama, The Sopranos. "A pattern of unstable relationships. Affective instability, it means intense anxiety, a joylessness. These people's internal phobias are the only things that exist to them. The real world, real people are peripheral. These people have no love or compassion. Borderline personalities are very good at splitting behaviour, creating bitterness and conflict between others in their circle." Flattened and dehumanising portrayals of the illness pervade films and online forums alike. Yet the label for all of its accumulated reductiveness, has offered me much in the way of clarity. What is diagnosis, if not a deeply imperfect yet necessary attempt to give voice to an aching body—one that roars out in primal, guttural, and illegible screams—begging to be understood?

My emotional life has always been rocky, full of swings, sharpness, and vicissitudes. On 'good' days, madness feels like blessed symphony, days when my blood feels golden. I am magnified, grown in my mind's eye, overcome with riotous fits of pleasure as ephemeral and fleeting as their opposite: I am carried aloft on waves of euphoria. In the shower, I catch a falling shampoo bottle and believe for a second I am developing superpowers. Butterflies are a good omen: I see them, and I know everything good is coming. My mind races so much that the world slows to gelatine in comparison. I leave it behind. Moments later, and without warning, something within me cracks open, and I am brought low and to a place of devastation. There are tears with seemingly no end. Mania and manna, despite surface appearances, share no etymological commonality—and yet I must surmise that both have divine roots.

Night terrors, along with sleeping and waking hallucinations, are common in people with borderline personality disorder. Perhaps trauma alters our brain in a way that makes us susceptible to night's irreality. I have spent almost all of my life attempting to hide the severity of my symptoms and ailments from the people I love. In my teenage years, before illness took hold of me so thoroughly, I flourished in academia, even as misunderstood and grotesque as I often felt (and perhaps because of it). I was pious and steadfast. Instead of worldliness and parties, I preferred, like an anchoress, to work late at night, sequestered away from the distraction of the outside world. Though my piety, a secondary school teacher and close mentor once appraised, derived from pride and not godliness. He was, of course, correct. My piety, even then, was a gentlemanly act of desperation: a veneer of respectability intended to cover up what I perceived as my filthy, corrupting unworthiness. I cannot tell you exactly when God forsook my body. It has long felt like a cursed, liminal space—a storehouse for ghosts and devils, an unholy alliance of ailments and violent cliches. Not suitable for sustaining life. A deep, maybe even infinite, well of pain. A personality disorder is a kind of pain that begins in the mind and worms its way into the body. But what I describe next is a pain that begins in the bodies of others and then possesses my own.

For as long as I can remember, observing (and increasingly these days, sometimes even just hearing about) particular kinds of visceral pain, the kind constellated in flesh, would cause me a sensation that I eventually came to understand as a corresponding pain. Not queasiness, nor discomfort—I am not a squeamish person. It is literal physical pain, triggered by what appears from my perspective to be real pain, and increasingly sometimes (as I have grown more troubled in all aspects) its depictions: lacerations, emaciation, maiming, scarring—bodily suffering. I have come to understand this is a neurological phenomenon known in some schools of thought as ‘Mirror Pain Synesthesia’—that is, in those schools of thought that regard it as synesthesia at all. It is sometimes referred to simply as 'pain empathy', 'mirror pain' or ' vicarious pain' and is characterised by a physical sensation of pain, usually reoccurring in the same areas, in response to physical pain. It is estimated to affect anywhere between 17 and 33% of the population. I once met a girl on a night out who had the same condition, who felt her mirror pain in the back of the arms and the chest, the same as me. There was so much I wanted to ask her. We lost touch, never spoke again, and I no longer remember her name. A few months ago, a homeless man stopped me at a bus stop to ask for some change for transport to a hospital. He had his bicycle with him, and an ambulance would not take it with them. He showed me a deep, carmine gash in his forearm. I gave him what little change I had and when he walked away, I doubled over in agony.

"He must have felt that he had lost the old warm world, paid a high price for living too long with a single dream. He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is and how raw the sunlight was upon the scarcely created grass."

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

GLASS

King Charles VI of France, ‘Charles the Mad,’ came to think he was made from glass. In January of last year, I was spiked and robbed in a club in Paris. This is what I came to understand anyway. What I know is I was found stumbling, incoherent and covered in vomit in the corridor of a hotel I had stayed in earlier that trip. My feet were bare, and my expensive Margiela shoes missing.

In one of our many conversations, a mental health practitioner tells me she believes I have some form of PTSD: the symptoms and severity of which only began to manifest in the months that followed. I now am often given to overwhelming, debilitating anxiety and panic. Fear where I once felt a glowing, rapturous confidence. Glass—brittle, cracked, exposing—where there once was shining steel.

Before the clutches of illness, Charles the Mad was once 'Charles le Bien-Aimé'—Charles the Beloved.' Illness distorts us; pain is, in all and to all senses, a maddening thing. His glass delusion was not unique; as odd and idiosyncratic as it might seem, it was once common amongst a certain set, a product of a certain age and set of circumstances.

On more than one occasion since Paris, I have been terrified that it has happened again: I have been spiked, and I face imminent, life-threatening danger. My instincts feel irreparably off-kilter. I trust few people, myself the least. I take extra, sometimes irrational, precautions, or I take none at all. Contradictions mount. I have always been a strange creature, and the events of this last year have made me stranger still. My eating habits grew erratic; I lost a considerable amount of weight. Days and nights spent looking over my shoulder. I live in a state of hypervigilance. Parties are difficult, clubs nearly impossible—they set my nervous system on fire. I experience cognitive distortions: warped patterns of thinking that render me overcome with a belief in social spaces that I am public enemy number one. I have tried, against all odds, to push through my symptoms, resisted the call of fear to become a hermit, and it seems every time I venture out, I pay doubly for it. At gatherings, I play-act unconvincingly at enjoyment and pretend I am at peace. Everything within me screams to get out, to get home. I fear being a mark. I fear I am a mark. The right words do not come so easily now. My decisions have grown more impulsive. I find it impossible to discern other people's intentions clearly; my mind scans all the time for hidden meanings, for threats real or imagined. Compliments feel like deceit, and whispers feel like plotting. My shoes betrayed me once; I await the dropping of the other.

Captured Arsinoe was so beloved by the crowd on crossing the pomerium—Rome's sacred, ancient boundary—that they stayed Caesar's golden hand and put her up in a temple. I have tried and failed to sublimate myself, to become a more charming, less abrasive creature, to satisfy others' whims and needs, to mitigate my every sharp and unbecoming edge. All this in the belief that if I am simply what the people I meet want me to be—perfectly compliant, humble, generous, and thoughtful—nobody could want to humiliate me or hurt me.

Where once being disliked felt like a discomfort, it now feels like an existential threat. Where there was measure (and if not measure, dissembling), there is now emotional incontinence. I can no longer hide my madness. Paranoia colours my world. In my own story, I have become a most unreliable narrator. I have dissected the events of that night in Paris a million times, and then a million more and never got any more clarity. What was the method of my spiking: shot glass or highball? When? Who? In the immediate aftermath, the full extent of that night's trauma was not evident to me. I laughed about it, identified the sitcom nature of the incident's particulars (my lost shoes, the hotel room), and delivered it in a punchline that made people laugh. It was only in the months that followed, in the fearful, spiralling descent that accompanied them, could I see just how much the incident had perhaps irrevocably fragmented something within my psyche.

Now the events of that night grow further and further away, the vague shape of an animal in a rearview mirror, forever cloaked in fog. I see them as both canon and apocryphal. As permanently altering as that night was, I will never know, with any meaningful clarity, the truth of what happened. I am a changed man. That is to say, I am diminished, and that is a kind of change. I sometimes ask myself: Is this karmic recompense for a past life or this present one? All mantras fall flat. A disembodied, toothless voice whispers: "I am not defined by my illness." My own voice roars back: "Of course, you are defined by your fucking illness!"

It is an astonishing thing to be so comprehensively ill, to live with defects both built-in and acquired. Can you distinguish flaw from nature, partition your heart from its illness? Is the soul all-encompassing, our faulty wiring and all? Or is the faulty wiring the blemish on our diamond immortal? If the latter rings true, would my physical death be a ritual of purification? Would it rid me of the sickness interred in my bones? In the last two years, the frequency of my suicidal ideations has increased severalfold. I think perhaps more than I ever did about the method. I admit this not for sympathy but for clarity. I have stayed alive in many ways as a courtesy; there are ties that bind—love deserved or not—anchoring me to this life. To kill myself would be to unravel multiple lives at the cutting of a single thread. To kill myself, I understand on some instinctive, primal level, would be a perverse act in a world in which people far less fortunate, less safe, less blessed, struggle for life, freedom, and open air. Make no mistake: I know that I am loved, have felt the hands, the heat, the words, and the sweat of it. But love on its own has long not been enough to sustain me, especially when experienced—felt—as the piteous polar end of an obligation, one I have only ever felt undeserving of.

O, ungrateful, unhappy, accursed child.

"If anyone who was suffering, in the body or the spirit, walked through the waters of the fountain of Bethesda, they would be healed, washed clean of pain."

— Tony Kushner, Angels in America: Perestroika

THE TOWER

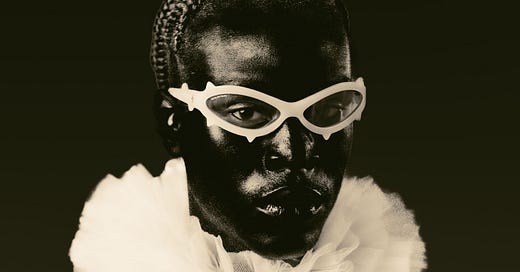

Only fantasists believe pain is beauty; the truth can be such an ugly thing. If this essay feels uneven, that is because it is. This essay is filled with things I have not said aloud. There are gaps in this essay, made up of things that I will perhaps never be able to say. This is the first time I have married all these unfortunate truths together without the cover of verse or comedy. There is an undeniably bitter irony that such ugliness occurred when I was in Paris seeking beauty, to indulge in the bread and circuses of fashion week. I once naively thought that, like a balm, outward beauty, airs and graces—many and splendid vanities—would heal from the outside in: a panacea of charm that would wash me clean. I realise now the deep and unsettling errors of my calculations. Pain, unchecked, unreckoned, unhealed, overwhelms and corrupts the host. There can only be a masking; no amount of physical beauty, of performed, perfumed princeliness can dislodge the violent aching at the core of one's soul. Beauty cannot be medicine for the abuses we have suffered. I thought if the clothes could not make the man, then perhaps they would hold him together—halt my unravelling. I have never in these three decades of my life felt more 'beautiful', been told by more people and institutions that I embody its arbitrary and exterior virtues, than this present moment. Yet all the while my insides have turned to pitch, tar, and decay—cold, barren, and inhospitable as winter's night.

“Don’t let ‘em say I killed myself for love."

— Ian McEwan, Cloud Atlas

There is not much in my heart left unturned. The turbulent events of these last few years have stolen what peace I had. If this essay may be evidence of anything, it is that Paris was not the beginning of my problems, but rather, a particle collider of traumas past and present. I have tried, unsuccessfully, to revert to behaviours, haunts, and happinesses of old. My triggering failures have confirmed a painful reality: there can be no reprisals nor reprising. My past—and past selves—cannot be amended nor repeated. I must forge new valour, build myself up from base clay, and begin again. Break with the past. Sometimes, the cost of healing—of transformation—is a radical disruption of our status quo, a seeking-out of help, professional and otherwise. My life up to this point has been marked by pain, consumed by it. Pain has made a prison of my life. On the precipice of thirty, and on the ledge of a high tower of madness, I face a choice, both spiritual and practical: heal or die. And this is my choice. I refuse to be some passive receptacle for pain—mine or anyone else's. I refuse to be its clay-jar, factory, or propagator. This is an oath: words by which I wish myself to wellness. Unburdening yourself is the work of a lifetime, and there can be no half-measures. Memoiristic writing often opens up post-facto and adds a satisfying symmetry to devastating events that they can only have in hindsight. The past here is not simply prologue: it is as much behind me as it is my today. As much a history of my mind and body as it is a theory. I am still living this, and will still, when you read these words, be living it. I do not write from some imagined place of wellness; I write to you from the present depths of my illness, which, on my worst days, still threatens to consume me whole.

I am not naive about what publishing these words means. To be honest about one's mental illness (especially that of great severity) is to encourage whispers and intimations about one's fitness for social and public life, to provide ammunition—spoken and unspoken— in fights and arguments, to invite pity—wanted, warranted or not. It is to grant access to one’s detractors of a most sharp weapon fashioned against you. But my truth is a flaming sword, and I wield it now to never let it be wielded against me again. There are no guarantees. I do not know that I can be made whole; there can be no promise of a happy ending. But I know that life is too precious a thing to be given up so easily.

What sustains me now is not certainties, but possibilities. All illness, be it cancer or the common cold, blinds us to possibilities of tomorrow—forecloses upon them. We cannot see beyond its present and narrow walls. We feel as though we have always been, and will always be, ill. To heal is to necessarily believe in possibilities. With this, and with everything within me, I say goodbye to these past decades of unhappiness, a lifetime of searching for love outside my body. I surrender myself to the fact of my illness and surrender the story of my illness to the world. Let it be known that my sanity has been hard-won. I clamber now out of this abyss, write myself out of the fetters and vast isolation of my pain, towards the light.

"I believe that a lost ship, steered by tired, sea-sick sailors, can still be guided home to port."

— Affirmation, Assata Shakur

this must have been doubly liberating and terrifying to write - I really understand the repetitive impulse to practice beauty rituals and using outward appearances as armour. I think most of us are stuck in that loop even though it never cures that deepseated 'aching' that you mention. But we move! (towards the light)